Materiality (auditing)

Materiality is a concept or convention within auditing, accounting, and securities regulation relating to the importance/significance of an amount, transaction, or discrepancy.[1] The objective of an audit of financial statements is to enable the auditor to express an opinion whether the financial statements are prepared, in all material respects, in conformity with an identified financial reporting framework such as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). The assessment of what is material is a matter of professional judgment.[2]

- "Information is material if its omission or misstatement could influence the economic decision of users taken on the basis of the financial statements. Materiality depends on the size of the item or error judged in the particular circumstances of its omission or misstatement. Thus, materiality provides a threshold or cut-off point rather than being a primary qualitative characteristic which information must have if it is to be useful."

- Percentage of pre-tax income or net income (i.e., 5% of average pre-tax income (using a 3-year average));

- Percentage of gross profit;

- Percentage of total assets; (i.e.,1/3% of total assets);

- Percentage of total revenue; (1/2% of total revenues);

- Percentage of equity; (i.e.,1% of total equity);

- Blended methods involving some or all of these definitions (e.g., use a mix of the above and to find an average);

- "Sliding scale" methods which vary with the size of the entity. (i.e., 5% of gross profit if between $0 and $20,000; 2% if between $20,000 and $1,000,000; 1% if between $1,000,000 and $100,000,000; 1/2% if over $100,000,000)

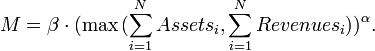

- A concave function, such as the "gauge" formula. Gauge is a measure of materiality that experiences a decreasing returns to scale as opposed to the other traditional quantitative metrics aforementioned. The concave nature of the function leads to a lower materiality threshold (which implies less tolerance for misstatement) as the company becomes larger because more users are relying on the financial statements. Although the formula varies, a typical structure is as follows:

a non-zero, non-negative constant; usually

a non-zero, non-negative constant; usually

-

a constant that is between zero and one, i.e.

a constant that is between zero and one, i.e.

for each asset or revenue account, transaction, etc.

for each asset or revenue account, transaction, etc.

Using different means to quantify materiality causes inconsistency in materiality thresholds. Since "planning materiality" should affect the scope of both tests of controls and substantive tests, such differences might be of importance. Two different auditors auditing even the same entity might generate differing scopes of audit procedures, solely based on the "planning materiality" definition used.

Defining materiality alternatively or otherwise, It is an expression of relative significance or importance of a particular matter in context to financial statements.(by Mortian 2011)

Alternatively, one could argue that rather than being a dollar amount developed by the auditor based on their professional judgement, materiality is a market phenomenon that must be discovered by the auditor through research activities. This interpretation is supported by the phrase "is material if its omission or misstatement could influence the economic decisions of financial statement users". Thus, the auditor must determine what amount does influence the decisions of financial statement users via a variety of methods, and potentially average those methods in an attempt to estimate the real monetary amount of materiality (which can never be known since it is simply the collective sentiment of all investors, creditors, managers, and regulators).

Auditors could conceivably ask the audit committee or board of directors to determine materiality since these groups represent investors and creditors. Another approach might involve developing a sensitivity analysis model that attempts to measure changes in a company's stock price as a function of changes in financial performance - thus revealing what monetary amounts investors perceive to be actionable. In contrast, materiality may be an amount that is important for regulators in some industries. For example, if a regulatory body has declared it is only interested in violations exceeding a particular monetary amount, this number may form the basis of determining materiality.

For an entity with a relatively small number of creditors, investors, managers and regulators, the auditor can simply determine materiality with direct inquiries made to these constituencies. Averaging the materiality amounts provided by these constituencies may lead to audit efficiency, however using the smallest materiality amount noted during the inquiry process ensures that even the most conservative constituent is satisfied with the relevance of the audit findings.

Qualitative materiality

Materiality also has a qualitative aspect. This refers to the notion that a misstatement or omission of information can be significant to the users of the financial statements due to the nature, rather than the size, thereof. An example is an important disclosure that is omitted from the financial statements.

Where materiality fits into the audit process

Materiality is quantified and considered twice during the audit process: first during the planning phase of the audit (when it is referred to as "planning materiality"), and second during the concluding phase of the audit (when it is referred to as "final materiality").

The assessment of planning materiality is required for risk assessment purposes (simply put: a material mistake holds risk for the auditor and the auditor should plan and perform the audit in such a way that he is likely to detect such mistakes). At this point in the audit the auditor has not performed any testing as yet. Hence, if he opts to quantify materiality using one of the common rules listed above, he has to apply the percentage to financial information that does not relate to the period under audit (such as prior period information) or untested financial information does relate to the period under audit. The auditor's decision in this regard required the application of judgement.

If the auditor opts to quantify materiality using one of the common rules, he should amend his quantification of planning materiality during the testing phase of the audit if he then establishes that the size of the company is significantly different from what he expected during the planning phase. Such a change should be documented, along with the impact thereof on planned testing.

The quantification of final materiality is commonly done using the same common rules, but the auditor (having completed testing) can now use tested financial information for the period under audit for the calculation thereof.

Materiality in governmental auditing

Materiality in governmental auditing is different from materiality in private sector auditing for several reasons.Most importantly, due to the format of state and local government financial statements under GAAP, the AICPA Audit Guide for State and Local Governments requires auditors to consider materiality by "opinion unit" rather than for the financial statements taken as a whole. The Guide defines opinion units as follows:

Government-wide level (three units):

- Governmental activities;

- Business type activities; and

- Discretely presented component units in the aggregate.

- General fund (always a major fund);

- Other major funds determined for government funds or enterprise funds. Each major fund is an opinion unit. If there are no major funds, then there will be only two opinion units—the general fund and the remaining fund information; and

- Remaining fund information, consisting of all other nonmajor governmental and enterprise funds, internal service fund type, and fiduciary fund type. (This will generally always be present, although the individual components and size will change between governmental entities.)

Moreover, the primary users of government financial statements are different: the citizenry and the parliament in the public sector versus investors in the private sector. It is important to identify the primary users since materiality reflects the auditor’s judgment of the needs of users in relation to the information in the financial statements.

Finally, in government auditing, the political sensitivity to adverse media exposure often concerns the nature rather than the size of an amount, such as illegal acts, bribery, corruption and related party transactions. Qualitative considerations of materiality are therefore different from in private sector auditing, in which qualitative considerations are focused on the effect on earnings-per-share, executive bonuses or other risks that are not applicable to governments. Qualitative materiality refers to the nature of a transaction or amount and includes many financial and non financial items that, independent of the amount, may influence the decisions of a user of the financial statements.

While rules of thumb mentioned in the section above are commonly applied to state and local government financial statements, government auditors may also use different means to quantify materiality such as total cost or net cost (expenses less revenues or expenditure less receipts). In a cash accounting environment, total expenditures is often used as a benchmark.

No comments:

Post a Comment